The Explanation Of This Famous Icon Will Give You A Deeper Understanding Of The Trinity

by Garrett Johnson

A highly creative piece, Andrei Rublev’s Troitsa (Russian for Triune or Trinity) hails from the summit of a more-than-thousand-year-old iconographic tradition. As you might have surmised, it is a Trinitarian interpretation of Gen 18:1-16, the episode in which “three men” visit Abraham and Sarah and promise them a son.

While no Christian would ever formally deny the importance of the Trinity, it is always healthy to question whether this importance has the impact on our daily lives that it should. I once heard the story of a professor of Theology who asked his students: “If I were to tell you today that we have discovered new texts of the bible and of the Fathers of the Church that reveal that our One God is, in reality, two people and not three, how would you react? Would what change in your life?”

If the Holy Trinity is merely an object of abstract theological debate, then such a change would not change your life much. If, however, the Holy Trinity is not simply a concept for us, rather a referral to our living relationship with God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit, then, in responding to the question, we should be jumping out of our chairs to defend the three People that we know and love!

Thus, more than an explanation of the Trinity, in today’s post I would like to try to invite you to, in some fashion, open yourself up and experience the fact that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are indeed real and insistingly call us to participate in their loving communion.

How Andrei Rublev’s Triotsa Explains The Trinity

1. The Desire for God

So often when we think of the Holy Trinity, we prepare ourselves for an onslaught of complicated concepts. Instead, before making attempts at understanding the Trinity, we should desire the Trinity.

In the words of Oliver Clément: “God is absolute beauty because he is absolute personal existence. As such, he awakens our desires, sets it free and draws it to himself.” Whenever speaking of desire, we must always remember that it is God who first desired (and continues to desire) us and our own desire originates in him.

The beginning, thus, of all spiritual life is in intensifying this desire, in stoking the flame, in asking the Holy Spirit to make it burn. “Blessed is the person whose desire for God has become like the lover’s passion for the beloved.” (John Climacus)

Again Clément: “It is not a question of thinking about the Trinity, but in it, starting from the Trinity as the unshakeable foundation of all Christian thought.”

2. The Unartistic Reverse Perspective

At first glance, the flat sides, rectangular edges and the general perspective of this icon is in glaring contradiction with the rules of linear perspective. For those accustomed for a more realistic depiction, this might be considered as some form of “crudely illiterate drawing.”

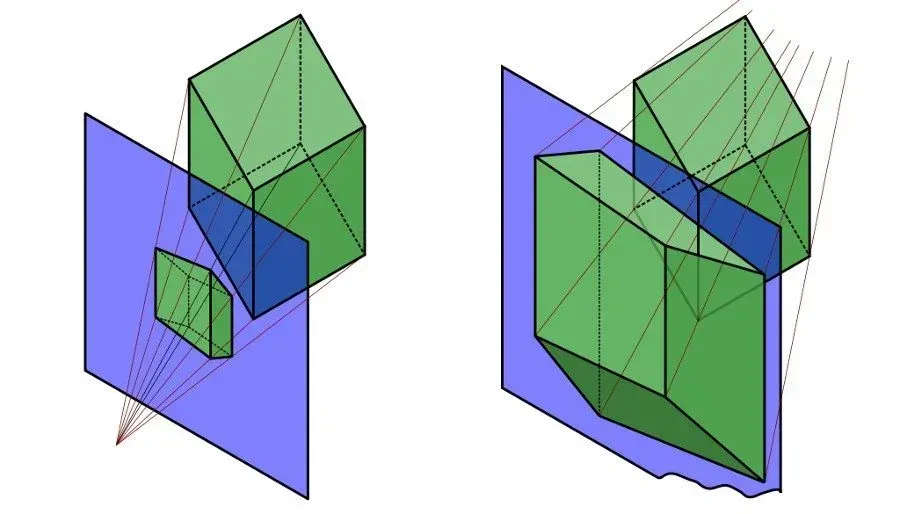

What we are looking at is a common technique in Icons called the Reverse Perspective. Visually speaking, this means that objects farther away from the viewing plane (see image below) are drawn as larger, and closer objects are drawn as smaller. Lines that are parallel in three-dimensional space are drawn as diverging against the horizon, rather than covering as they do in linear perspective (Wikipedia). As such, many of the objects seem oddly distorted.

Here are two other images that might aid in understanding:

“In the pictures above the focal point is the red star. On the left is a linear perspective. Here the lines of convergence surround the viewer and converge on a focal point “within” the picture. This creates the effect we are all familiar with when looking at paintings, the sense of looking “through” the picture as if looking out a window. On the right is a reverse perspective. The focal point is “outside” the picture, placed on the observer. The lines of the picture move out from the picture to converge upon the viewer.” (Experimental Theology)

Much more than an artistic technique, this perspective, if we are open to it, serves as a mentor in the school of the Christian perspective of reality. In the words of Bunge:

“Like the Church’s preaching of the word, icon painting makes use of its own principles. It consciously submits to its own rules and thus renounces much that is essential for profane painting. So it rejects what the world considers to be natural, or central perspective, which issues from the standpoint of the beholder, and choose what can be considered the unartistic reverse perspective, which forces the beholder to surrender his own standingpoint, his sense of distance.”

Put simply, the icon offers a perspective in which we are not the center. It is not we who submit reality – above all, the Divine Reality – to our own criteria, rather it is we who freely submit ourselves to the tremendous and fascinating beauty of the only true God who has revealed himself in Jesus Christ.

It is not we who illuminate God, rather the contrary. And this is precisely the dynamic that we witness in this icon:

“Likewise, neither are shapes and objects illuminated from outside, rather they have their own source of light within themselves.”

The key spiritual attitude in all of this is openness; we mustn’t try to force things, rather allow ourselves to be guided by the Holy Spirit in an “unfolding of revelation” in the teaching of the Church.

3. Context: The Feast of Pentecost

In the time of ultra-specialization and selfies, we have a tendency to concentrate on the particular and forget the whole. While beneficial in some senses, we can easily lose sight of the big picture and end up doing violence to the particular, especially when dealing with matters of faith. Every truth of faith is intimately intertwined and can only be fully understood within the body as a whole (here we could speak of the analogia fidei or “analogy of faith” which means the coherence of the truths of faith among themselves (Cfr CCC 114)).

When looking at any icon, we must not forget that its “place” is not a gallery (in this case, the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow). Its home is the liturgy. Bunge explains that:

“each icon of this format not only has its set place within the church building, but also its position in the Church year. in the case of the Troista, its place in the church is to the right of the central doors of the iconostasis, and its place in the church year is the Feast of Pentecost.”

The association between this Icon and the Pentecost takes place above all in the Russian Orthodox Church (I believe). The feast that celebrates the descent of the Holy Spirit is understood as the fullness of the revelation of the triune God. When and where this transition took place exactly is up for debate. Still, it is clear that the Holy Trinity in the form of Abraham’s three angelic visitors has become the festal icon of Pentecost. Look on the right side of the door in the picture below:

Iconostasis of the Trinity Cathedral of the Trinity-Sergius Lavra

Image from Olaroma

A Prophetic Foreshadowing

Prudence recommends that we note the fact that in the New Testament the Father and the Son remain hidden behind signs or symbols such as “voice” or “dove.” The inner workings and dynamic between the Three Persons is, of course, the mystery of mysteries and utterly unknown to us. As such, when contemplating the emblems and holy signs of the Old Testament, we are not looking for them to reveal the Holy Trinity as such, but serve rather as a “prophetic foreshadowing of the way in which the divine persons make themselves accessible now to the faithful, and indeed only them”. What is depicted is, therefore, only – and that “in an image” – the economic Trinity; its being for us.”

4. The Trinity Is One

The Catechism 253 is clear in saying: The Trinity is One. We do not confess three Gods, but one God in three persons, the “consubstantial Trinity”. The divine persons do not share the one divinity among themselves but each of them is God whole and entire. In the words of the Fourth Lateran Council (1215), “Each of the persons is that supreme reality, viz., the divine substance, essence or nature.

Symbolizing the fact that the three divine persons are of equal essence, we see:

– All three angels are the same in form and size

– All three carry the same staves in their hands

– All three sit on the same type of throne

– Each figure is clothed in the same types of garments – chiton and himation – which are individually distinct.

– The characteristic tone of the garments works with a limited palette of colors: purple, pale green, and the one color that is common to all three – an intense blue.

5. The divine persons are really distinct from one another

The Catechism continues in number 254 to explain: “The divine persons are really distinct from one another. God is one but not solitary.” “Father”, “Son”, “Holy Spirit” are not simply names designating modalities of the divine being, for they are really distinct from one another. They are distinct from one another in their relations of origin: “It is the Father who generates, the Son who is begotten, and the Holy Spirit who proceeds.” The divine Unity is Triune.

The Monarchy of the Father

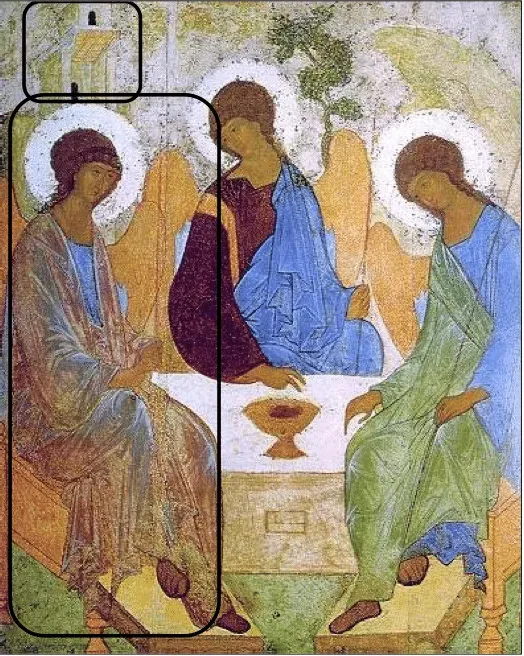

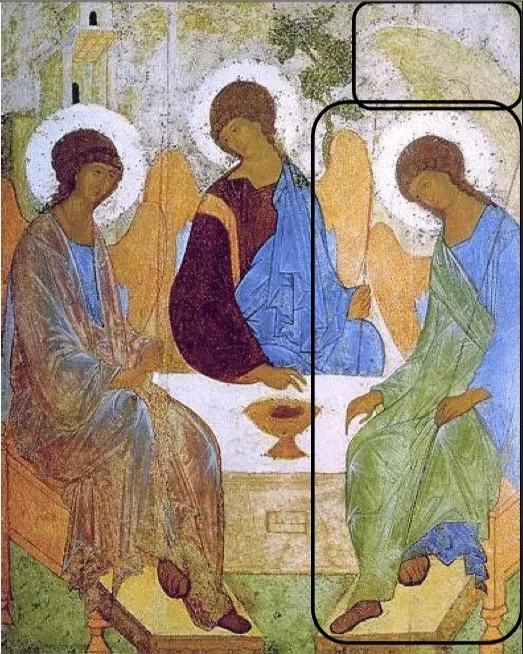

While the traditional icons of this episode usually accentuated the central angel (the Son) through its frontal attitude and often its size, here Rublev does something different:

The central angel and the one on the right incline towards the one on the left and look towards it, while the one on the left looks towards the one on the right, giving the indication of relationship between the three persons.

As such, it is the angel on the left that becomes the center of the relationships. This follows the Oriental tradition which considered the source of the unity and of the Godhead to be, not an essence lying behind the persons, but the person of the Father.

The Angel on the Left – The Father

When speaking of icons, in reality, one doesn’t say that he or she has “painted” an icon. They are “written” and “read”, going from left to right. Let’s now take a look at each individual angel, beginning on the left, and try to recognize the particular aspects. We can distinguish the angel on the left from the others seeing that:

– He alone sits upright while the other two incline towards him.

– Seeing that the Father is still invisible for us, His form is almost completely veiled, allowing us to catch only a glimpse of the radiant blue (symbol of divinity) of His chiton. We can only hope to see him from “behind” through the beauty and wisdom of His creation which is here represented by the mantle. The mantle bears royal colors: gold and red with a greenish reflection, symbol of life.

– Both hands bear a firm grip on his stave which is pointed towards the earth. All authority of the heavens and the earth belong to Him.

– The house, rising immediately behind him, points to the Father, for “in my Father’s house are many rooms” (Jn 14:2). It is also a symbol of hospitality, seeing that Abraham and Sarah were recompensed for the hospitality that they offered. What does this tell us about the importance of hospitality?

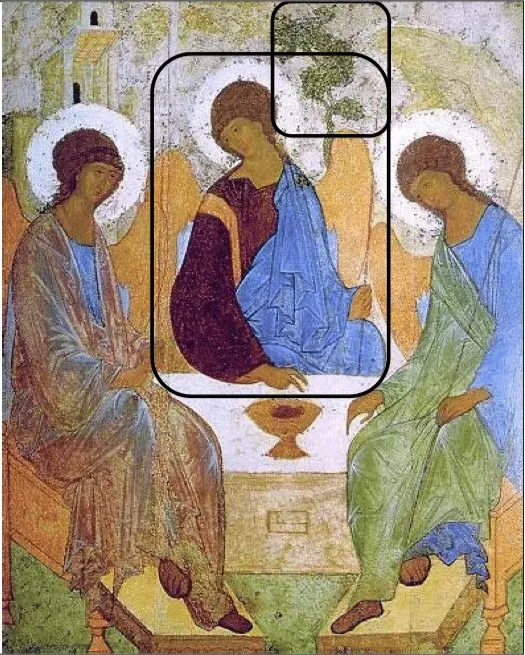

The Angel in the Middle – The Son

In the Icon, we can discover the following distinguishing characteristics of the son:

– He wears a dark purple chiton decorated with two – one of which is visible – stripes worked with gold. The costly purple and gold represent his being the “anointed of God,” king and prophet in one. The reddish brown color represents the earth and therefore his humanity. Christ is fully God and fully man.

– While the azure blue chiton of the Father is scarcely visible, that of the angel representing the Son is the prevailing color. This is because it is Jesus the Son that has revealed his “glory” which he has as the “only-begotten of the Father”. The disciples have seen and touched this (Jn 1.14) and the mission of every disciple is to bear testimony of this fact.

– The tree that rises behind the Son is a symbol of both the Tree of Life (from Genesis) and the Wood of the Cross. On the Cross the son transforms this tree of death into a tree of life whose fruits are passed on to us through our baptism in the Holy Spirit.

Let us always remember that we too are called to follow Christ along the paradoxical path of the cross that carries the sufferings of this world and allows this, through the Holy Spirit, to be transformed into new life.

The Angel on the Right – The Holy Spirit

The Holy Spirit is always a tricky one to depict. While his personal being has been revealed, his countenance has not. The only thing we know about him is through his relationship to the Father and the Son.

– Like the Son, the Holy Spirit is inclined towards the Father, from whom he proceeds according to the teaching of the Bible (Jn 15:26).

– Like the Son, the chlamys is worn in such a way that leaves an arm free. Here, instead of the right arm, it is the left. Those follow the line of thinking proposed by St. Irenaeus who said that the Son and the Spirit are equally the two “hands” of the Father, through which he works everything.

– Like the son the heavenly azure blue is clearly seen.

– We also discover in his chlamys a pale green which, in Russia at least, is the liturgical color of Pentecost. Here the idea is that green represents new life in the Spirit who is the “Giver of Life” and who transmits and transforms our lives through our baptism. We see this same pale green on the ground on which all three figures find themselves.

– Finally, behind the angel we see a rock protruding. Like the Son and the Holy Spirit, the rock seems to be bowing down towards the authority and glory of the Father. We are invited to do the same.

– The rock can be understood as a symbol of earth, whose “face is renewed by the Spirit”. Earlier copies of the icon show that the rock was originally cracked which would lead us to recall the rock that was split by Moses’ staff, causing living water to flow out (Ex 17.6).

– The rock/mountain is also a privileged place to encounter God. There, heaven and earth embrace one another as they did when Moses encountered God on the mountain. It is a place there is often difficult to reach, requiring a certain silence, asceticism, and renunciation of the daily comforts the world and its routines offer us. We all need to keep an eye out for these “mountains” in our lives.

6. Postures and Gestures

The Original Painting

Copyists and retouchers have made significant changes over the years. Originally, the Son’s hand was pointing towards the Holy Spirit, instead of the blessing gesture that we now see (Bunge says that he has seen what he considers to be the original gesture in older copies). The Son’s right hand seemed to point at the chalice; yet, at the same time, it points beyond towards the Spirit.

The artist’s attention was thus more directed at the Spirit. This is confirmed by the Father’s posture and gesture as he is looking at the Spirit, to whom his right hand, raised in blessing, is directed. The Spirit also seems to corroborate this in the fact that he humbly bows his head before the Father. His right hand also seems to want to underline this movement.

The Decisive Moment for our Salvation

Bunge’s consideration aside, I personally enjoy those who interpret this scene to be the moment when the Father decided to send the Son, through the Holy Spirit, to save humanity (us).

As we see in the image below, it is the Father, who is at the origin of it all, who calls the son and indicates the cup of sacrifice in the center of the table. The Son comprehends the Father’s will (to become man’s bread of life) and accepts, bowing his head and blessing the cup.

The Holy Spirit, also known as the Consoler, also accepts the will of the Father. He rests his hand on the table as he looks towards the Father, indicating his obedience to the Son (no one can call upon “Jesus Christ” without the Holy Spirit) and His trustful abandonment to the Father.

7. The Symbol of Sacrifice

With careful observation, one can note how the middle angel seems to be contained within the shape of a cup whose contours are formed by the other two angels. Similar to the reflection just mentioned, here we see how the act of salvation is one of the Holy Trinity. As the Filarete, metropolitan of Moscow, once commented in 1816:

"The cup, a point of convergence between the three, contains the mystery of love of the Father who crucifies, the love of the Son who is crucified, and the love of the Holy Spirit who triumphs with the force of the cross."

While the three figures form a circle, it is not closed in on itself. It is a circle of communion which opens and offers space for another. While their gaze is aimed towards one another, due to the reversed perspective, the faces are in some fashion facing the observer as well. As such, the spectator (that’s you and me), is invited and welcomed to participate as the fourth link in this mystical chain.

8. The Altar and the Eucharist

As we have just seen, in this Trinitarian circle of love, there is always space for another, and open space in which we are invited not only to observe but to participate.

At the center of the encounter, there is a table/alter where we also see a small box/window. This space is where relics of the martyrs are deposited.

When asking ourselves how we are called to participate, here and now, the icon invites us to participate in the celebration of the Eucharist (the altar) and to live our lives as martyrs, as witnesses of the resurrection who, following the school of Jesus, are willing to give our life for others and for the faith.

For this post, I have followed the presentation of Gabriel Bunge in his book The Rublev Trinity.

I have also consulted and used the images from the PDF offered by the Parrocchia di San Giorgio.